- Catalog No. —

- OHS Lib 639.22 U58r 1894

- Date —

- 1894

- Era —

- 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Government, Law, and Politics, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- U.S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries

- Regions —

- Coast Columbia River

- Author —

- Marshall McDonald, Investigations in the Columbia River

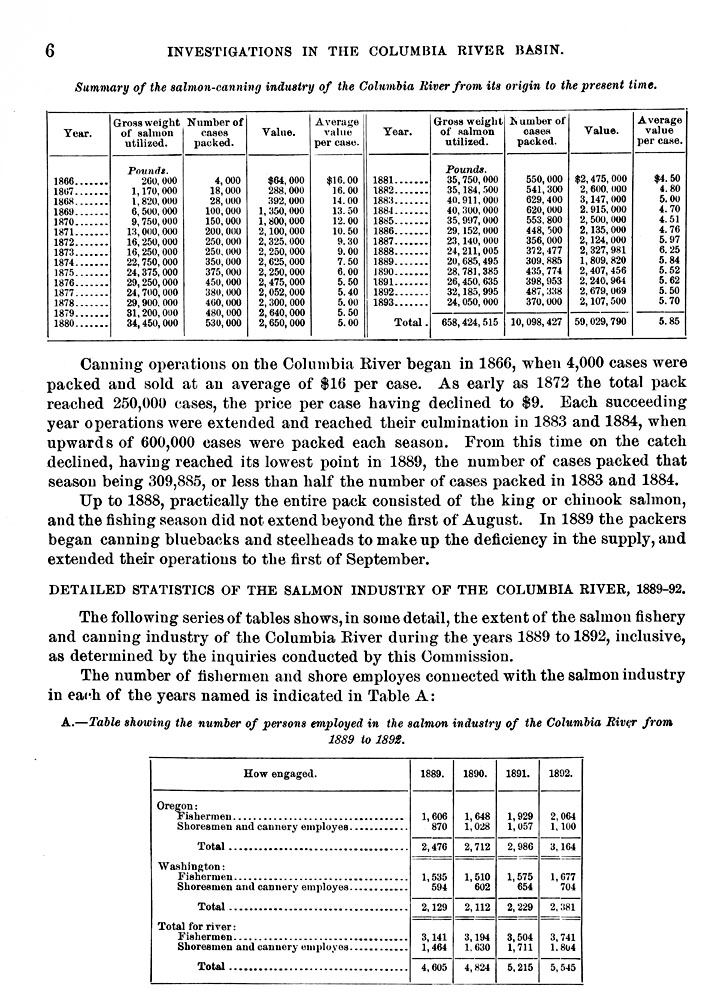

Salmon Decline, 1894

This document is an excerpt from an 1894 report by the U.S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries Marshall McDonald. It describes the decline of salmon in the headwaters of the Columbia River during the late nineteenth century.

The Columbia River was once one of the most productive salmon rivers in the world. Scholars have estimated that between 7.5 and 16 million adult salmon returned annually to the Columbia River prior to white settlement, providing an abundant food source and trade good for the Native peoples of the Columbia River Basin.

Although non-Indians began commercial fishing in the Columbia in the 1820s, efforts remained limited due to the distance of markets and the lack of long-term storage technologies. The advent of salmon canning in the mid-1860s solved these problems, revolutionizing the region's salmon industry. Canning allowed the long-term storage of salmon so that it could be transported to markets around the world. The technology led to the explosion of the commercial fishery in the 1870s. In 1875 there were fourteen canneries on the lower Columbia; five years later there were twenty-nine. The number of canneries peaked at thirty-nine in 1883, after which it became clear that the fishery was overcapitalized.

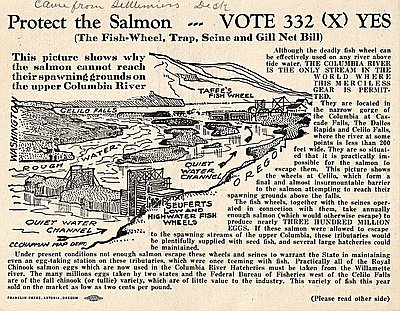

Concerns that the Columbia's salmon runs were being overfished began to surface in the late 1870s. By 1894, when the document reproduced above was published, it was evident that many stocks were disappearing. Hardest hit were spring and summer chinook, which made up the bulk of the salmon pack in the early years of the fishery. The author notes that as spring and summer chinook declined, "packers began canning bluebacks [sockeye] and steelheads to make up the deficiency in supply, and extended their operations to the first of September."

Although McDonald blames the "great commercial fisheries prosecuted in the lower river" for the decline of salmon, habitat degradation was also a significant factor. Irrigation, mining, logging, water pollution, and the construction of tributary dams all played roles in the decline of the Columbia River Basin's salmon populations. Sockeye populations, for example, plummeted after dams were built at the outlets of many of the Columbia River Basin's most productive rearing lakes around the turn of the century.

The construction of large mainstem dams on the Columbia and Snake rivers beginning in the 1930s exacerbated the decline of salmon that had begun fifty years earlier. As of 2006, thirteen stocks of salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River Basin were listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Further Reading:

Lichatowich, Jim. Salmon Without Rivers: A History of the Pacific Salmon Crisis. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1999.

Smith, Courtland L. Salmon Fishers of the Columbia. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1979.

Taylor, Joseph E., III. Making Salmon: An Environmental History of the Northwest Fisheries Crisis. Seattle: University of Washington, 1999.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006.

Related Historical Records

-

Protect the Salmon - Vote 332 (X) Yes

This card was distributed by the Fish Conservation Committee, a political group organized to promote a 1908 initiative that sought to ban fishwheels and other forms of commercial salmon …

-

The Dalles Dam

This 1963 photograph of The Dalles Dam was published in the March 1968 edition of the Portland Chamber of Commerce’s monthly magazine, Greater Portland Commerce. The accompanying article, …

-

Dams and the Onset of the Modern Age

If there is a significant moment that marks the onset of the modern age, it may be August 6, 1945, the day an American B-29, the Enola Gay, …