- Catalog No. —

- CN 004857

- Date —

- n. d.

- Era —

- 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Government, Law, and Politics, Native Americans

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Columbia River

- Author —

- Unknown

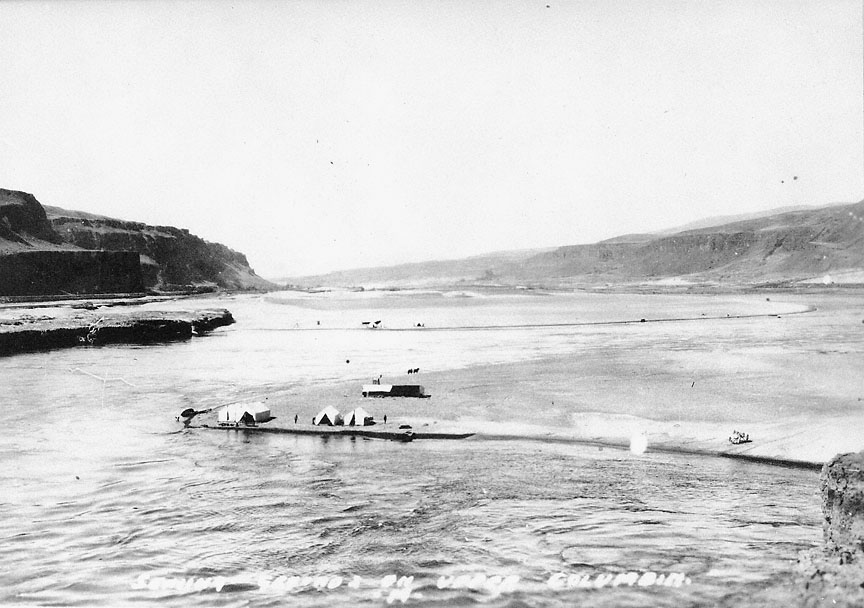

Looking Downstream to Celilo

This undated photograph shows non-Indians fishing for salmon along the free-flowing and meandering Columbia River just upriver from Celilo Falls. Writing on the photograph indicates that the fishers are horse seining, a fishing strategy that caught large amounts of salmon by using horses to haul nets through the river toward shore.

An archaeological excavation near The Dalles, Oregon has provided scientists with evidence of salmon fishing within the Columbia River Gorge dating back approximately 10,000 years B.P. (before present). According to oral traditions and the Congressional testimonies of a number of the region’s Native American peoples, like the Wasco and Wishram and some bands of Klickitat, Yakima, Walla Walla, and Umatilla, they have fished the waters of the Gorge since time immemorial.

The narrowing of the river into fast-moving channels at Celilo Falls made fishing predictable and highly productive. During the spring and summer salmon runs, thousands of people from across the region gathered around Celilo to fish, trade, gamble, partake in festivities and to pursue potential marriage partners.

Indian tribes reserved the right to fish at Celilo Falls and their other “usual and accustomed places” in treaties with the United States in 1855. After the start of the Columbia River’s salmon canning industry in 1866, competition between Indian and non-Indian fishers in the Gorge began to intensify. During the 1890s Indian fishing rights were challenged directly by non-Indian fishers, who blocked Celilo fishing sites along the Washington side of the river with state-licensed fish wheels—large rotating wooden and wire fish nets, powered by river currents, that were used on the Columbia River from 1879 to 1934. But, the U.S. Supreme Court, in United States v. Winans, upheld tribal rights and forced the removal of these fish wheels in 1905.

Indian fishers continued to fish at Celilo until the completion of The Dalles Dam flooded the falls and the portion of the river seen in this photograph in 1957. To compensate the tribes for the loss of Celilo Falls, the U.S. government paid a total of $27.2 million in damages to tribal governments.

Further Reading:

Cohen, Fay G. Treaties on Trial: The Continuing Controversy over Northwest Indian Fishing Rights. Seattle, Wash., 1986.

Cone, Joseph and Sandy Ridlington. The Northwest Salmon Crisis: A Documentary History. Corvallis, Oreg., 1996.

Dietrich, William. Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, Wash., 1995.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2003.

Related Historical Records

-

Chinook Indians Seining

This photograph was taken by John F. Ford, a photographer who had commercial studios in Portland and Ilwaco, Washington, between approximately 1900 and 1914. It shows a group …

-

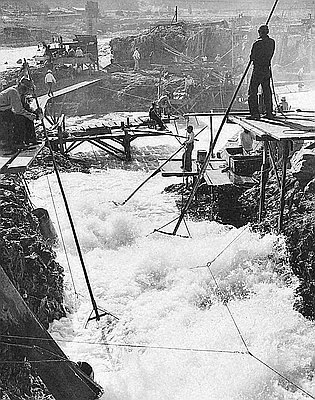

Indians Fish at Celilo Falls

Celilo Falls was an important center for native trade, culture, and ceremony. For at least 11,000 years, tribes throughout the region, and from as far away as the …

-

Chief George Charley's Seining Crew

This photograph shows Chief George Allen Charley (center in vest and white shirt) and his seining crew in Pacific County, Washington, around 1907. Chief Charley was chief of …