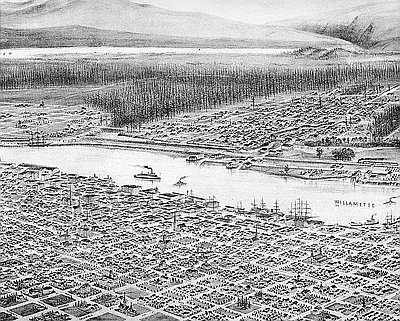

In the decades following the Civil War, Oregon’s population underwent a tremendous increase, from 90,923 residents in 1870 to 413,536 in 1900. During the same period, the state saw its isolation from the activities and influences of the eastern part of the nation rapidly disappear with the connections provided by the transcontinental telegraph (1864), the railroad (1883), and improved mail service. An influx of new immigrants, as well as easier access to ideas, publications, and building materials from other areas, contributed to marked changes in the appearance of Oregon buildings.

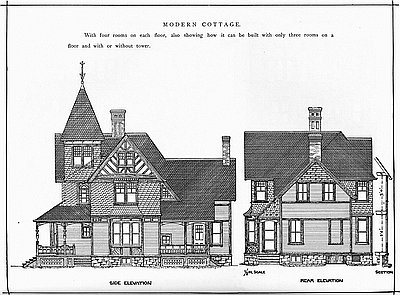

Among the new ideas were those associated with architectural styles and ideas of what was appropriate in the way of ornamentation and building features, considering the purpose of the building, its cost, and its location. The architectural styles that appeared in succession during the late nineteenth century were most apparent in the visual appearance of buildings, more so than in their plan or materials. These stylistic ideas arose in tandem with the developing professionalization of architecture, which during the late nineteenth century moved toward a system of academic study and professional licensing. Architectural ideas were also widely distributed through publications, including professional journals such as Chicago’s Western Architect (1882), as well as popular magazines and plan books. Some architects issued plan books that depicted fashionable building plans that were available by mail order.

Architectural style was more than mere decoration. Certain styles were advocated as particularly suitable for certain types of buildings, as the Gothic Revival was said to be especially suited for churches and small residences. Gothic Revival drew its inspiration from medieval European church architecture. Translated into wood, the style was characterized by steep gable roofs, windows with pointed arches, a distinct vertical emphasis, and elaborate brackets and bargeboards done with a jigsaw. Despite admonitions from the new profession about suiting a style to particular uses, adaptation was pervasive and many builders pushed beyond the limits that architects set. Buildings designed by self-taught architect Louis Scholl at the army’s Fort Dalles (ca. 1857) and at Fort Simcoe in Washington Territory, were based on designs that he derived from Architecture of Country Houses, by Andrew Jackson Downing, who was an early proponent of the Gothic Revival style.

Other distinctive architectural styles from the later decades of the nineteenth century included the Italianate, Second Empire (or French Mansard), Stick, Eastlake, Queen Anne, and Shingle styles. Examples of these styles were common in Oregon, especially in wooden residential construction. Like earlier styles, they derived from historical models but they were adapted to different, locally available materials and to new uses. The development of lathes and jigsaws made it easy and inexpensive to turn milled lumber into elaborate decorative pieces. Even simple workers’ houses could be treated with the lacy wooden trim and scalloped shingles that made them stylish Queen Anne cottages. While fashionable buildings were designed by the practitioners of the emerging architectural profession, a great many more were put up by local carpenter-builders who melded their accumulated working knowledge with the fashionable designs they saw in publications.

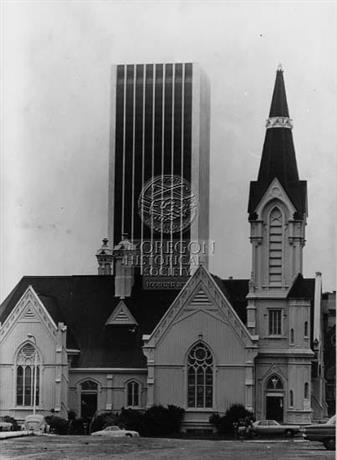

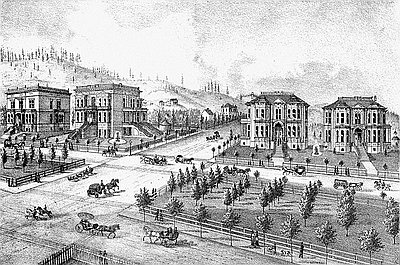

Paralleling national developments, Oregon saw the rise of architecture as a recognized profession in the 1870s and 1880s. Some of the earliest notable practitioners were William W. Piper, Warren H. Williams, Justus Krumbein, and Whidden & Lewis (William M. Whidden and Ion Lewis). Among them, they practiced in several popular architectural styles. Piper is particularly noted for designing two major brick buildings in the Second Empire or French Mansard style—the Marion County courthouse in Salem (1873) and Deady Hall, the first building on the campus of the University of Oregon in Eugene (1873-1876). Warren H. Williams created the plans for Portland’s Calvary Presbyterian Church (1882), a wooden confection in the Gothic Revival style, and the elaborate Italianate residences of brothers Ralph and Isaac Jacobs (1880). The Jacobs houses “were so influential that hundreds of homes in Portland were constructed in the 1880s with similar layouts, proportions and detailing,” wrote architectural historian William J. Hawkins III.

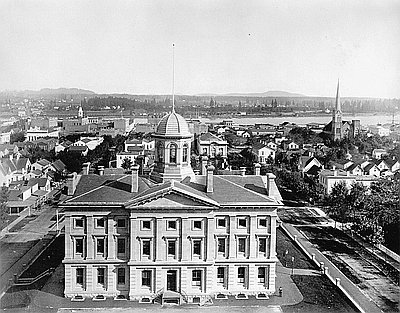

Architects from other areas did major work in Oregon as well. The Pioneer Courthouse, designed by Alfred B. Mullett of Washington, D.C., rose on what was then the outskirts of downtown Portland in the early 1870s. The oldest standing federal building in the Pacific Northwest, the Pioneer Courthouse was designed in the Italianate style and was built of sandstone from quarries at Tenino, Washington Territory. While this use of stone was uncharacteristic for the time and place, it characterized the work of the designer as well as the need to emphasize the authority of the federal government. It still holds a strong symbolic position in Portland and Oregon.

Another Portland building brought to Portland two architects who remained to become prominent practitioners. As part of his transcontinental railroad ambitions, capitalist Henry Villard engaged the well-known New York architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White to design hotels in Portland and Tacoma and a terminal in Portland. In 1882, Villard brought partner Charles F. McKim to Portland and purchased a lot for the hotel immediately west of the Pioneer Courthouse. McKim, Mead & White selected William M. Whidden as the project architect, and they proposed to build the hotel in the Queen Anne style. Financial difficulties stopped the project in 1883; but when it resumed in 1887 under new auspices, Whidden was asked to come to Portland to finish it himself.

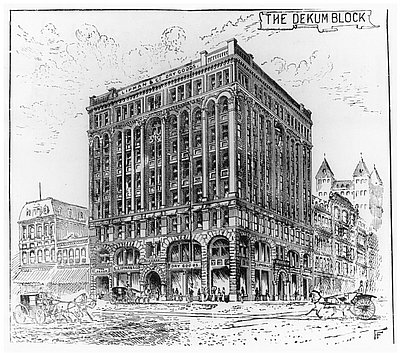

Whidden brought Ion Lewis with him. The new Whidden & Lewis firm not only completed the Portland Hotel (1890), but went on to design other prominent buildings, including the first public library (1890) and City Hall (1895). These buildings made significant use of stone and exhibited modern design elements that reflected the emerging Renaissance revival style. Rival firm McCaw, Martin & White introduced Richardsonian Romanesque style to the city through the New Market Annex (1889), First Presbyterian Church (1891), the K.A.J. Mackenzie residence (1892), and the Dekum Building (1893-1894). As architectural historian Marion Dean Ross noted, “By the middle of the nineties, the architects in Portland, if not all of Oregon, were abreast of current styles in other parts of the country.” In fact, the lag was relatively short, thanks to the speed with which publications and ideas crossed the continent in the 1890s.

© Richard H. Engeman, 2005. Updated by OHP staff, 2014.