- Catalog No. —

- Journals 4. Thwaites : 327-329

- Date —

- April 27, 1806

- Era —

- 1792-1845 (Early Exploration, Fur Trade, Missionaries, and Settlement)

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Exploration and Explorers

- Credits —

- Lewis & Clark Journals. Reuben Gold Thwaites. 1905.

- Regions —

- Columbia River Oregon Country

- Author —

- Meriwether Lewis

Yelleppit and the Walla Wallas

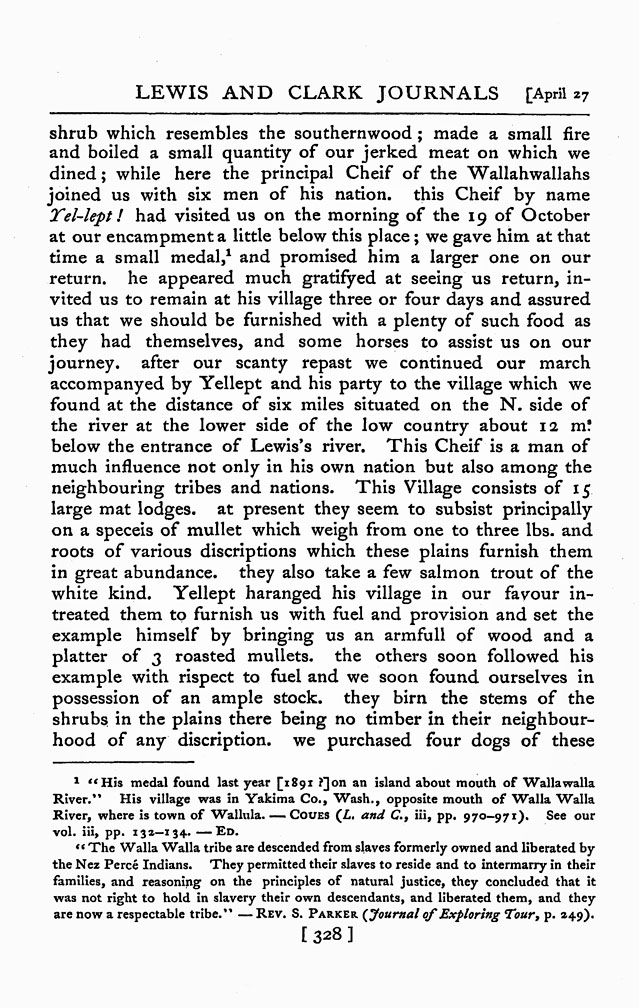

This excerpt from Meriwether Lewis’s journal describes the Corps of Discovery’s encounter with Walla Wallas and their headman Yelleppit (Tamtappam). After crossing the Umatilla River—which Lewis calls the “Youmalolam”—on their return to St. Louis, the “much fatigued” explorers stopped to eat. While encamped, they were met by Yelleppit and six others. Lewis and Clark recognized the headman from the previous fall, when the Expedition had stopped at his village near the mouth of the Walla Walla River. The captains had given Yelleppit a small peace medal and had promised to spend a few days with him the following spring.

Little is known about Yelleppit aside from what is in the journals. When the explorers met him in October 1805, Clark described him as “a bold handsom Indian, with a dignified countenance about 35 years of age, about 5 feet 8 inches high and well perpotiond.” It is unlikely that Yelleppit was his name. Yalípt is a Sahaptin word that means “trading friend,” a formal social relationship among Plateau peoples whose economy was based in large part on trading, gifting, and other forms of exchange.

Several months later, on April 27, 1806, Lewis wrote that Yelleppit was “a man of much influence not only in his own nation but also among the neighbouring tribes and nations.” The headman was interested in the American explorers, who he viewed as potential trading partners, and he persuaded them to stay at his village for a couple of days. The Walla Wallas entertained Expedition members with dancing and music, and a nearby village of Yakamas joined in the celebration.

Before the captains took their leave of the Walla Wallas, whom Lewis described as a “friendly honest people,” Yelleppit presented Clark with a “very eligant white horse” and asked for a copper kettle in return. The captains had already given away all of the kettles they could spare, so Clark presented Yelleppit with his sword instead, as well as some gun powder and a hundred musket balls. It would be twelve years before the Walla Wallas established lasting trade relations with Americans. In 1818, the Northwest Company built a trading post named Fort Nez Perce—later known as Fort Walla Walla—at the mouth of the Walla Walla River.

Written by Cain Allen; revised 2021

Further Reading

Hunn, Eugene, E. Thomas Morning Owl, Phillip E. Cash Cash, and Jennifer Karson Engum. Cáw Pawá Láakni/They Are Not Forgotten: Sahaptian Place Names Atlas of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla. Pendleton, OR: Tamástslikt Cultural Institute, 2014.

Lewis, Meriwether, and William Clark. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Vols. 5 and 7, edited by Gary E. Moulton. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988, 1991.

Pinkham, Allen V., and Steven R. Evans. Lewis and Clark Among the Nez Perce: Strangers in the Land of Nimiipuu. Washburn, ND: Dakota Institute Press, 2013.

Ronda, James P. Lewis and Clark Among the Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984.

Rude, Noel. Umatilla Dictionary. Seattle: University of Washington Press, in collaboration with the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, 2014.

Related Historical Records

-

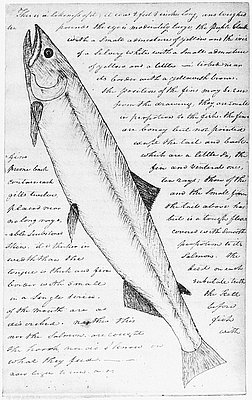

Clark's Drawing of White Salmon Trout

This is a copy of a sketch made by William Clark in February 1806, while Expedition members were at Fort Clatsop near the mouth of the Columbia River. …

-

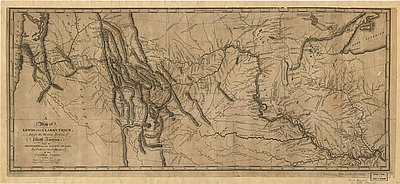

Map of Lewis and Clark's Track

This map, titled A Map of Lewis and Clark's Track across the Western Portion of North America from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean, published in 1814, is …

-

Death of Meriwether Lewis

The death of Meriwether Lewis in the fall of 1809 has long been a subject shrouded in mystery and controversy. This much we know: on September 4, 1809, …