- Catalog No. —

- OrHi 51017

- Date —

- circa 1922

- Era —

- 1921-1949 (Great Depression and World War II)

- Themes —

- Black History, Government, Law, and Politics, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality, Religion

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- Unknown

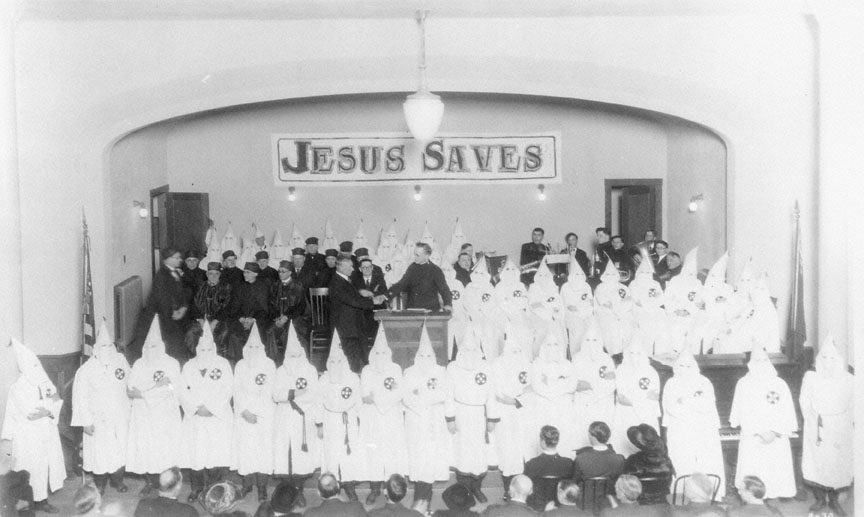

KKK in Oregon

In this photograph from the early 1920s, probably taken in Portland, robed and hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan shared a stage with members of the Royal Riders of the Red Robe, a KKK auxiliary for foreign-born white Protestants. The Klan’s ideas of what it meant to be an American developed during World War I as a reaction to the perceived threat to national unity posed by the influx of non-Protestant, non-English-speaking immigrants.

Many Americans felt increasingly threatened by cultural shifts caused by changing demographics in the country and by the popularity of communism abroad and at home. New patriotic and nativist groups became culturally and poltically active during the post-World War I period. Congress enacted the Emergency Quota Act in 1921 that set limits on how many people could enter the United States. In 1924, it passed the Johnson-Reed Act, which attached quotas to all nationalities seeking to enter the country. Within the U.S., the migration of Southern Blacks to the industrialized cities of the North was viewed as an economic and racial threat by the North’s predominantly white labor base; and Catholics and Jews were still viewed as “foreign” religions that threatened the fabric of American life. The Oregon Klan advised voters to supportWalter M. Pierce for governor and the Oregon Compulsory Education Bill, both on the ballot in 1922. Pierce won his election, and the bill, which would have eliminated private schools (particularly those run by Catholics and other religious groups), was approved by voters. The U.S. Supreme Court determined that the Oregon Compulsory Education Act was unconstitutional in 1925.

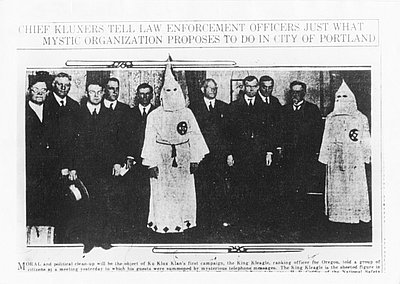

The Klan's philosophy of “100 percent Americanism” rested primarily on three attributes: belief in a political ideology of white supremacy, adherence to Protestantism, and the superiority of native-born Americans. Given Oregon’s history of racial exclusion and the fact that almost 90 percent of the state’s population in the early 1920s was native-born, white, and Protestant, Klan organizers had little trouble enrolling new members. The Klan played to the economic, religious, and political concerns of “ordinary” middle-class citizens by stressing the threats posed by immigrant labor, “foreign” religions, and communism. Recognizing this fact, the Klan organizers directed their initial recruiting efforts at local law enforcement officials, Protestant clergy, and members of fraternal groups such as the Masons and the Elks.

Membership in the Klan was limited to native-born white men, but to the organization's reach the KKK established auxiliary groups such as the Royal Riders of the Red Robe, for white Protestants born outside the United States, and the Ladies of the Invisible Empire for women. The Oregon affiliates helped create in the early 1920s one of the strongest state Klan organizations in the country.

Written by Dane Bevan, 2004; revised 2021

Further Reading

Gordon, Linda. The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition. New York: Liverwright, 2017.

Horowitz, David. Inside the Klavern: The Secret History of a Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s. Carbondale, Ill.: 1999.

Saalfeld, Lawrence J. Forces of Prejudice in Oregon, 1920-1925. Portland, Ore.: 1984.

Toy, Eckard Vance. The Ku Klux Klan in Oregon: Its Character and Program. M.A. Thesis, University of Oregon: 1959.

_____. “The Ku Klux Klan in Oregon.” In Experiences in a Promised Land, edited by G. Thomas Edwards and Carlos Schwantes. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1986, 269-286.