- Catalog No. —

- OHS Museum 65-530

- Date —

- 19th Century

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration), 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Arts, Environment and Natural Resources, Native Americans

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Columbia River

- Author —

- Unknown

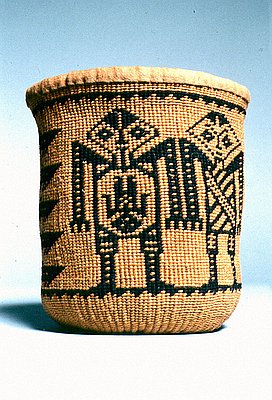

Carved Wood Mortar

This wooden mortar is of Wasco or Wishram design. Prior to moving to the Warm Springs Reservation, the closely related Wasco and Wishram peoples lived on opposite sides of the Columbia River, near the now-submerged stretch of river once referred to as Five Mile Rapids and Celilo Falls, at the narrowest portion of the Columbia River Gorge. The Wishram lived on the northern side of the river, while the Wasco inhabited the southern side.

Mortars were used by Wasco and Wishram communities—and by indigenous peoples worldwide—as they prepared their foods, collected during the spring, summer, and fall, for winter storage. Meats, roots, seeds, and nuts were mashed into powder with the aid of a stone pestle, a hand-held, club-shaped implement with a slightly rounded end. Sometimes, in far-flung locations, visited seasonally for the collection of roots, mortars were carved into locally-accessible large stones or downed logs, then left in place, to lighten transportation loads to and fro. At more permanent village sites, such as along the Columbia River, where food was available for most of the year, portable mortars were constructed of hardwood.

Compared to their female counterparts of the Columbia Plateau, who typically contributed roughly half of the community food supply, Wasco and Wishram women gathered and prepared fewer roots, berries, and nuts for their villages. Much of their time was instead spent helping to prepare the enormous volume of salmon that Wasco and Wishram men caught from the Columbia River at various rapids and at Celilo Falls, the most productive salmon fishery in the Pacific Northwest and perhaps all of North America. After drying the salmon, women pounded a portion of it into a fine powder, added some fish oil, and then mixed it with dried berries to produce a salmon pemmican. Pemmican was highly nutritious, easy to pack, and if made properly, could be stored for a year or more. Dried salmon and pemmican were greatly valued in trade throughout the Pacific Northwest. Wasco and Wishram women traded them for already-prepared foods such as dried elk and deer meat, biscuits and loaves of camas, wapato, biscuitroot, and bitterroot, and other non-edible trade goods.

Further Reading:

James, Caroline. Nez Perce Women in Transition, 1877 – 1990. Moscow, Idaho, 1996.

Hunn, Eugene S. Nch’i-Wana “The Big River”: Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. Seattle, Wash., 1990.

Ackerman, Lillian A., ed. A Song to the Creator: Traditional Arts of Native American Women of the Plateau. Norman, Okla., 1996.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.

Related Historical Records

-

Pounding Fish, Wishham, 1910

This photograph shows a Wishxam (also spelled Wishham or Wishram) woman making pounded salmon near Celilo Falls. It was taken by Edward Curtis in 1910. The sexual division …

-

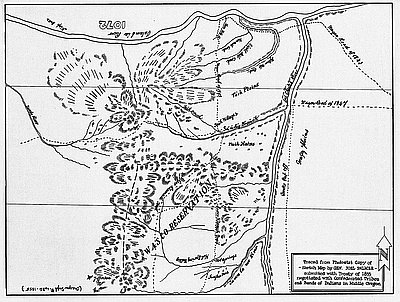

Wasco (Warm Springs) Reservation Map, 1855

From 1854 to 1855, Joel Palmer, the superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon Territory, negotiated nine treaties between Pacific Northwest Indians and the U.S. government. Many Indians agreed to …

-

Wasco-Style Sally Bags

This Wasco Sally Bag, named “Sturgeon Greet the Babies,” was made by Pat Courtney Gold, a member of the Wasco Nation of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm …